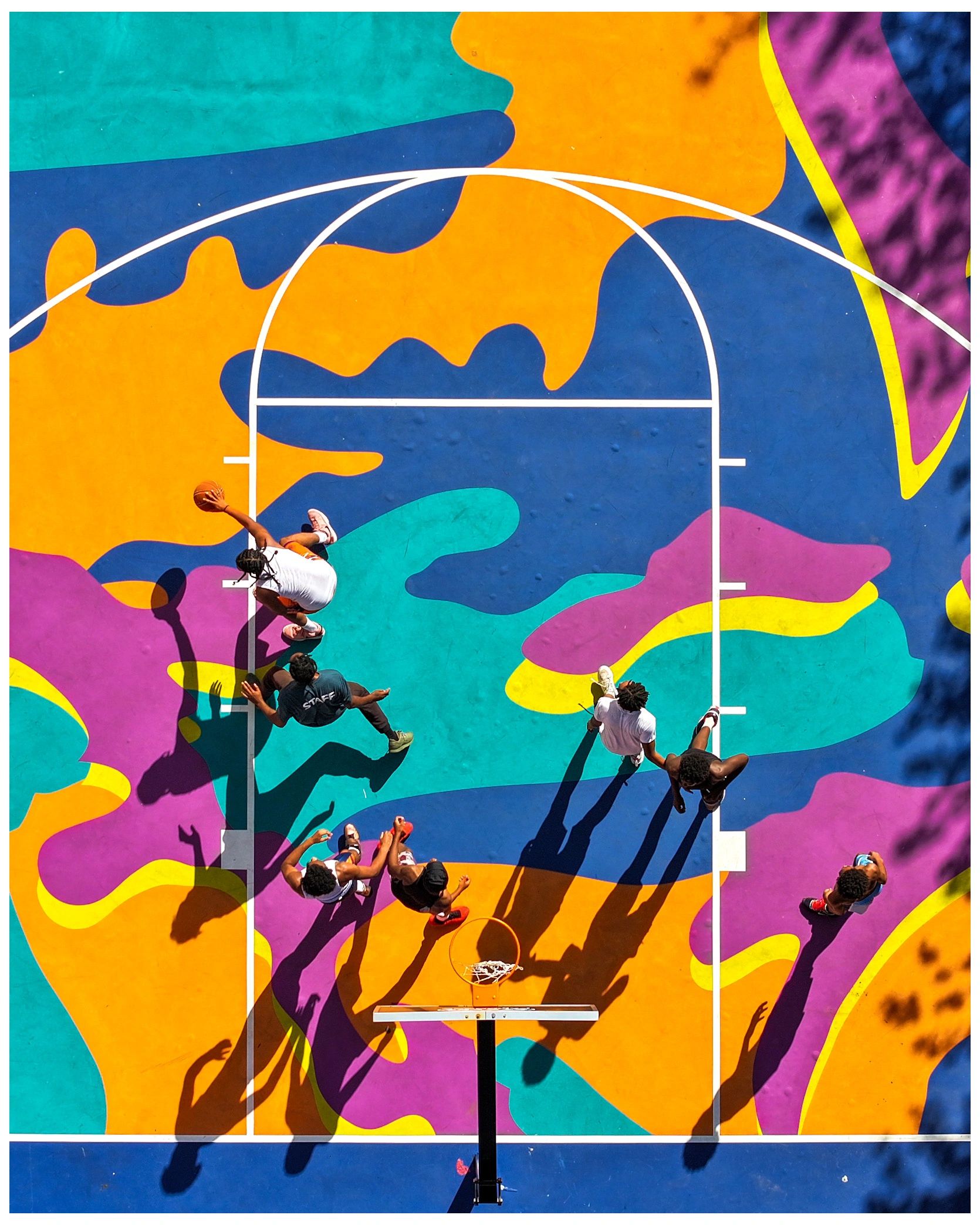

Andy Warhol, Camouflage, Lower East Side Playground, New York, NY 2025

Photo: © Shelton Hawkins

Reproduction of Andy Warhol’s Camouflage created in 2025 by Project Backboard © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

ANDY Warhol's Camouflage in the East Village, NYC

Words and images, unless otherwise credited by Blake Gillespie of Sacred. All reproduction of Andy Warhol’s Camouflage created in 2025 by Project Backboard © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

The Lower East Side Playground basketball court is a protected space with its own natural and urban camouflage. The fenced-in park and community garden is lush with redwoods, elms, pin oaks, and a weeping willow at the center; all of which obscure the court from various angles. Among its urban camouflages the basketball court on the mid-block park hugs the high brick wall of the East Side Community High School. The lower third of that wall is caked in decades of graffiti. Now, the court itself is camouflaged in the print artwork of Andy Warhol. The newly-minted camo court doesn’t militarize a public space (thankfully), but offers yet another dimension to Warhol’s use of abstraction on his own terms.

Photo: © Kevin Couliau. Reproduction of Andy Warhol’s Camouflage created in 2025 by Project Backboard © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

For the students of East Side Community High School, setting their own terms is part of being that age and the social experiment of high school. In that sense, placing Warhol’s Camouflage print on the basketball court offers an opportunity for introspection and inspiration alongside a renewed place to play. The French etymology of camouflage (1821) is believed to be a loaner verb from the Italian camuffare or possibly the older camāre which respectively translate to “disguise or make unrecognizable” and “to cast a spell, charm.” The environment of the Lower East Side Playground now carries a deeper resonance for local teenagers who are in that precarious balance between blending in with community and defining their individuality. A place where they can cast temporary spells of camouflage as they imagine their futures.

Human camouflage is meant to evolve with shifting environments. Warhol himself reinvented himself many times, creating significant distance from his Byzantine Catholic roots as a son of Polish immigrants in Pittsburgh, to becoming a renowned commercial artist in the 1950s for clients like the Tiffany Co. and The New York Times, to transitioning into fine art and becoming the most famous artist in the nascent Pop Art movement of the 1960s. He accomplished all this as a gay man when being out was both taboo and criminalized in the U.S. That renouncement of heteronormative camouflage made him a gay icon. His most iconic Pop Art work is Campbell's Soup Can (1962), a ubiquitous inevitability in art. While his exploration of celebrity cultism produced portraits of Mao Zedong, Elvis Presley, Marilyn Monroe, Muhammad Ali, and Kareem Abdul Jabbar. He even tried to make his own icons through his managerial ties to the Velvet Underground and Lou Reed by producing their debut album, with equally iconic banana cover art, and enlisting them into his traveling multimedia performance art The Exploding Plastic Inevitable. Then there’s Nico and Edie Sedgwick who became the original it girls of downtown through Warhol’s films like The Chelsea Girls and Poor Little Rich Girl. But, no one in Andy Warhol’s orbit could eclispe Andy Warhol. His silkscreen on canvas self-portraits in his fright whig remain among his most famous works and took many evolutionary forms, last of which appeared in the Camouflage print series.

With so many iconic works to consider, Project Backboard’s selection of the lesser known, late career Camouflage print for a basketball court begs questions. Questions like why not a Campbell’s Soup Can? Or why not put a New York City basketball icon like a Kareem Abdul Jabbar’s Warhol portrait down? But, in the non-profit’s 10-years of service, they’ve maintained a sensitivity not just to the artists they work with (or in this case estate), but to the environment of the community. For instance, two courts in Harlem’s St. Nicholas Park feature prominent Harlem fine artists in Faith Ringgold’s Windows of the Wedding, #1 quilt court and Nari Ward’s Breathing Court. Project Backboard founder Dan Peterson was receptive to community input before selecting an artist for the Lower East Side Playground basketball court. His inspiration to approach The Andy Warhol Foundation For The Visual Arts, Inc came from a community member's suggestion that the potential court design consider the bark patterns from one of the park’s trees.

“When they sent me photos of the tree bark, I immediately thought of Andy Warhol's Camo works,” he says. “I knew that Warhol had connections to the neighborhood and couldn't help but wonder if he had thought at all about the bark on East Village trees while producing this series.”

Trees in New York City, specifically the East Village, aren’t often the first inspiration source that comes to mind in one of the country’s densest urban landscapes. New York City’s identity is more akin to the absence of green space. In a neighborhood more recognized for its rough ethos of black-painted dive bars and graffiti that covers the terrain from sidewalks to rooftops, it’s hard to notice the trees unless a missing pet flyer is posted to one. But, the artist’s eye works differently.

In looking at Warhol’s synthetic camouflages—which are among Warhol’s final finished portfolio works before his untimely death in 1987—we see an artist evolving the military pattern to fit his environment in the art world. Perhaps hinting to why he projected many of his Camouflage prints onto his face for the self-portrait series.

Maria Murguia, Assistant Director of Licensing at The Andy Warhol Foundation, noted that Warhol used the camouflage pattern as “a vehicle for visual play.” While much of Warhol’s work is discussed in Pop Art’s post-war American consumerism context, the Camouflage series is one of his few works that directly engages with a military image, while also remaining agnostic to political commentary. Murguia offers that “rather than commenting on militarism,” the Camouflage series transforms “a utilitarian design meant to conceal into something vividly aesthetic.” The result subverts a symbol of state power into a topographical field of abstraction.

In a sense, Warhol’s Camouflage prints reclaimed the military garb designed by 20th century artists back for the arts by demilitarizing the patterns in pinks, whites, reds, purples, blues, yellows and oranges. Only his Statue of Liberty screenprint in traditional army camo colors could be suggested as militaristic or political. But Warhol was infamously apolitical in his work and public discourse. In the history of the modern camofleur movement—still a relatively new artform in his lifetime—, he exists as a subversive who disregarded the implied warfare of the form, while still honoring its aesthetic.

Modern military camouflage didn’t enter Western strategy until French painter Louis Guingot invented the first camouflage jacket in 1914. Guingot’s camo print represented a simplification of nature with the intent to blend to one’s surroundings. While the prototype was originally rejected by the French military (and stolen, the returned prototype had a square cut from the fabric), the military enlisted Post-Impressionist artists as designers, or camoufleurs, like Lucien-Victor Guirand de Scévola and Jean-Louis Forain in 1916. It sparked a movement among American artists that was spearheaded by muralist Barry Faulkner, whose works line the National Archive Administration's Rotunda for the Charters of Freedom, and sculptor Sherry Edmundson Fry to form the New York Camouflage Society in 1917. Like their French counterparts, the War Department initially disregarded their expertise, but by late 1917, as hundreds more artists and architects joined the movement, the American Camouflage Corps was given official status. Their innovations were implemented in World War I. Artists continued to inspire camo innovations into the mid-1970s, but Murguia says Warhol’s camo prints were purely driven by his investigation of repetition, surface, and transformation. The result is a wholly detached product from its origins.

Warhol’s fascination with consumerism became part of the process when he collaborated with fashion designer Stephen Sprouse on a line of Warholian camo print jackets and blazers. Sprouse received licensing permission to use the camo patterns a week before Warhol died. Known for his mix of uptown sophistication with downtown’s punk ethos, Sprouse’s jackets represent some of the earliest use of camouflage in high fashion. That moment, which nearly didn’t happen, seems to set off a chain of events in which urban camo undergoes an evolution in New York City as the look captures the heightened sociopolitical environment of the 1980s through the Crack Epidemic, and the amplification of the War on Drugs into the 1990s. For the next fifteen years, the police become more militarized, and a counter-militancy enters the fashion of the hip-hop generation through rap groups like Boot Camp Clique and the artwork for Capone-N-Noreaga’s 1997 debut album The War Report. As Prodigy of Mobb Deep famously spoke to the conditions in New York City, “there’s a war going on outside no man is safe from.”

Photo: © Kevin Couliau. Reproduction of Andy Warhol’s Camouflage created in 2025 by Project Backboard © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

Andy Warhol’s ability to turn banal consumerism and mass media into conflicts between the traditions of high and low art continues to sustain relevance in camo apparel. By the late 90s, the Army-Navy surplus company Rothco [coincidentally founded as Rothenberg & Sons in a small loft on Great Jones Street in the Lower East Side in 1953] understood the emerging streetwear trends of hip-hop and skateboarding, and began producing camo variations in yellow, red, and purple that feel like descendents of Warhol’s Camouflage series. Urban camouflage, as Warhol had imagined it in 1986, had gone commercial.

Photo: © Shelton Hawkins. Reproduction of Andy Warhol’s Camouflage created in 2025 by Project Backboard © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

It’s not known whether Warhol was inspired by tree bark in the East Village, but his Camo series does present vibrant abstract topographies of synthetic and inorganic colors that would offer crypsis and mimicry to the urban landscape. One much like the East Village in the 1980s which was receiving an artistic makeover through the emerging artform of graffiti. In the Lower East Side, graffiti was warfare on the landscape, a subversive army against the city departments and privately enlisted scrubbers. Their guerilla tactics, which have evolved into propelling off the sides of buildings to bomb or throw up burners on heaven spots, account for the bureaucracy, red tape, and financial burden to hire buffers that give their art a longer public lifespan. Currently, district officials seemingly gave up the ghost in scrubbing and criminalizing the artform. To this day, that’s still the identity of the East Village.

In September of 2025, Project Backboard, with licensing permission from the The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts Inc, renovated the Lower East Side Playground basketball court with a Warhol Camouflage print. The chosen print contained no militaristic greens or tans. The terrestrial pattern of Warhol’s camo consists of royal blue, sea green, purple, pale orange and bright yellow. It looks like Rust-Oleum colored tree bark. Urban camouflage for the inner city youth who are still figuring it out.